Latest News

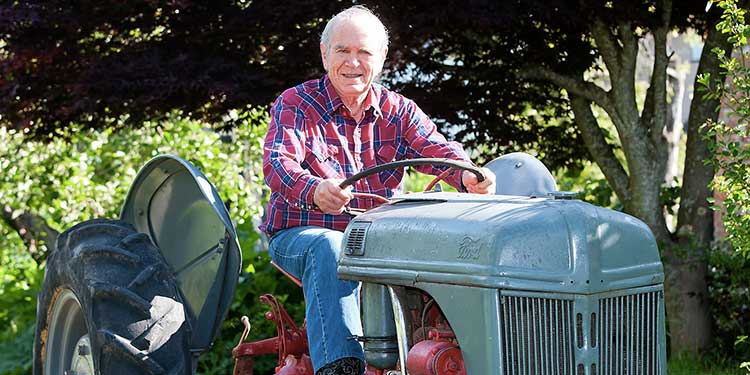

Spunky Steves carries forward family’s pioneering traits

On his 80th birthday, Harold Steves is busy

planting beans.

A historically late spring means Steves and

his wife Kathy have been busy trying to make up for lost time.

“We grow plants to raise seeds,” he explains.

“Kathy and I got involved because (local seed retailer) Buckerfield’s went out

of business. We had to start raising our own seeds.”

It’s not the first time Steves has had to

adapt. It defines his life.

Like his great-grandfather Manoah Steves, one

of the first settlers in the village named after him, Harold has persevered.

B.C.’s longest-serving politician, Steves has

been a Richmond city councillor for 47 years. True to what got him elected in

the first place, he remains as feisty as ever.

“I’m having too much fun (to pack it in),” he

laughs. “But It’s all health-related. I never say one way or the other (whether

to seek re-election) until a few weeks before an election.”

Steves says his plunge into the political

arena was very much unplanned.

“I wasn’t political at all,” he explains. “I

was going to UBC and taking agriculture. I was going to take over the (family)

farm. Then one day, in 1959, my dad came in saying we were going out of

business.”

Harold Sr., had learned that the farm had

been rezoned residential without his knowledge. This led to a desperate attempt

to save the farm and from there a lifetime in politics.

The original Steves’ farm, 400 acres in all,

was purchased by Manoah when he and wife Martha arrived in 1877, attracted by

the rich delta soil and tidal flats similar to his former farm in New

Brunswick. They also imported the first purebred Holstein dairy cattle into

B.C.

Harold was encouraged by a friend at

university to talk to the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation which later

became the New Democratic Party.

“They were basically a farm party and that’s

why I joined. To promote saving farm land. I’m still fighting that,” he said.

The dilemma also led Steves to lobby for what

would eventually become known as the Agricultural Land Reserve. Today, nearly

5,000 hectares (12,000 acres) or 39 per cent of Richmond’s land is within the

ALR.

“A friend of mine, who had a farm next to the

old Steveston High, and I went to a big farmer’s meeting at the old Brighouse

race track,” Steves recalls. “There were 200 or 300 people there. We got

(together with) a number of people in various parts of the Fraser Valley, who

were also concerned, and formed a committee.”

A few years later, Steves was able to get the

land bank proposal, which he drafted, onto the NDP convention floor. The

resolution passed.

Determined to have a policy enacted at the

government level, Steves, by then a Richmond city councillor, decided to seek a

seat as an NDP member of the legislature in 1973. He was elected, and the ALR

became reality.

As he was getting his feet wet in the

political arena, a young Steves—facing an uncertain future in farming decided

to become a school teacher. It was a career that helped support himself, Kathy,

who he met at UBC, and their five children. Ironically, all but one of the kids

wound up with careers related to agriculture.

It wasn’t trying to save farmland, but rather

stop the potential dumping of raw sewage into the Fraser River, that prompted

him to pursue civic politics.

“(Longtime Richmond activist) Lois Carson

Boyce got me involved,” he explains. “We got about 1,000 names on a petition

saying the city should build a (sewage) plant. We ran a slate of candidates in

the 1968 municipal election and I got elected.”

That led to forming, eight or nine months

later, what Steves believes was the first environmental group in Canada. Carson

Boyce chaired the group and Steves was its vice-chair.

“It was amazing when I look back,” he says. “We

got our sewage treatment plant.”

Steves’ zealous nature ultimately led to yet

another innovation—the first trail system in the province, while he was fearing a possibility of supertanker port on Sturgeon Banks.

“I’m proud of that,” he says. “My neighbour

had just come back from Sturgeon Banks. There were orange stakes in the ground

all the way to Garry Point.”

Today, Steves spends much of his day (when he’s

not busy attending to a community or city-related function) working on the

family farm. He retains a few acres, which is still zoned agricultural. That

includes the 100-year-old Steves home, being restored close to its original

state. He and Kathy raise Belted Galloway beef cattle, which graze on a grass

pasture on the property and on the salt marsh outside the dike. The seeds they

save from the produce grown on the farm are part of the Heritage Seed Program,

which preserves heirloom and endangered seeds, fruits, grains and herbs. This

practice dates back to his great uncle and grandfather, Joseph, who started the

first seed company in B.C. in 1888.

Richmond Mayor Malcolm Brodie says, “Harold

Steves has been a great contributor to the city for decades,” he says. “His

input and contributions have been far too far numerous to mention. His actual

contributions are far wider than that.”

Brodie says ‘agriculture’ is the first word

that pops to mind when one thinks of Steves, “but I think that’s only the

surface.“

“He has a very practical approach to issues,

and his knowledge of the history of our city adds a great deal to any

discussion or debate,” adds Brodie. “Harold is strong in his beliefs, and I

heard him say one time he is in favour of anything he thinks will make for a

better planet. I think that kind of sums up his approach.”